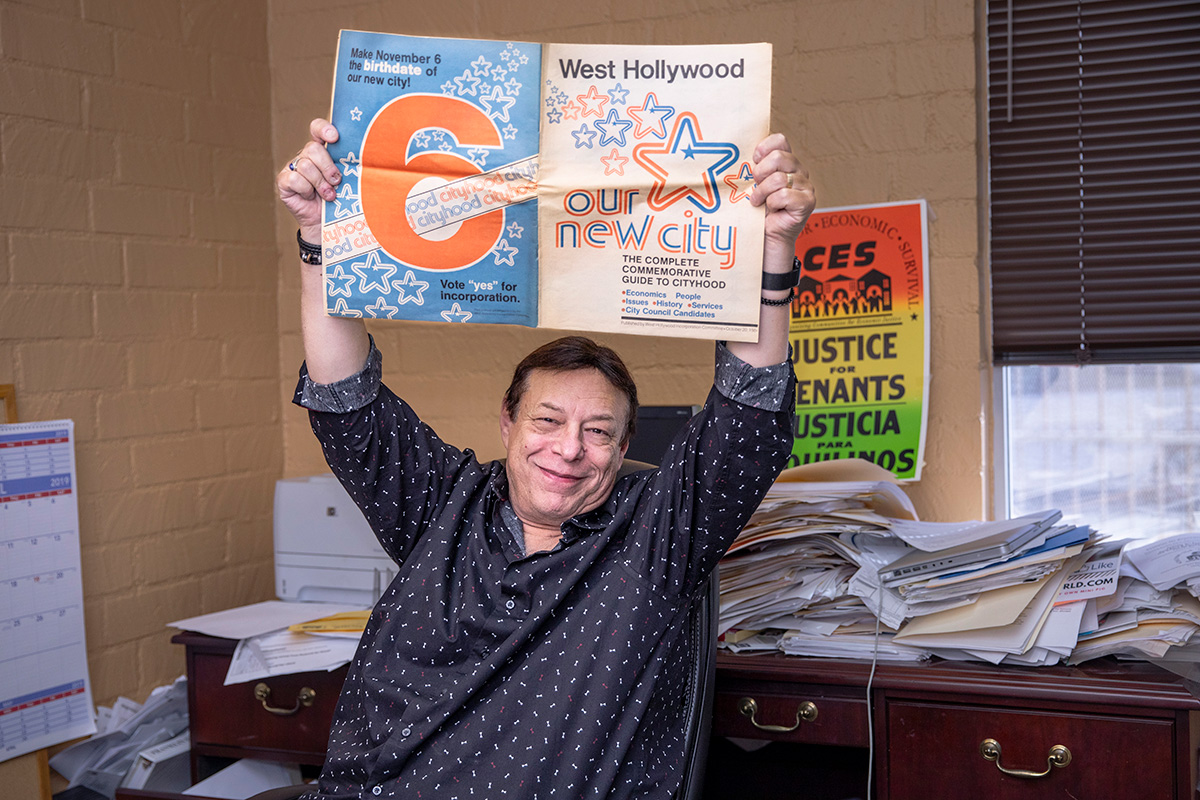

Larry Gross

“There is this Jefferson Starship song, ‘We Built This City [on Rock and Roll].’ When I hear that song, thinking of West Hollywood, all I can think of is we built this city on rent control.”

I would say Cityhood began in 1976 in the battle to win rent control in Los Angeles County. CES’s phones started ringing off the hook. That’s when developers and speculators discovered the Los Angeles area and were buying up apartment buildings left and right, putting a new coat of paint on them, and hitting people with three, four, or five rent increases within a year. There were no protections against eviction. Ed Edelman, a newish Los Angeles County supervisor at the time, was giving away variances to developers like after-dinner mints. That’s why West Hollywood became one of the most densely populated areas this side of the Mississippi.

During those years, West Hollywood renters packed the L.A. County Board of Supervisors meetings on a regular basis, facilitated by a bus line on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood that went directly to the Hall of Administration. It was a coalition effort from the start with the LGBTQ+ community, union activists, seniors, and others that pressured the supervisors for rent control. CES held rallies in Plummer Park where over 1,000 people came. These rallies were the first time that actors Ed Asner and Martin Sheen spoke politically. At one rally, we basically put it to Edelman that we need a date for the vote on rent control or else we were going to start a recall against him. During this time, I remember one day I got a call from George Chakiris, Bernardo from the movie West Side Story, asking about CES’s work. I went over to his house to talk about rent control and his Academy Award sat on his mantle. He then provided help to publicize one of our Plummer Park rent control rallies. At the rally, Martin Sheen asked everybody to join CES and fight for rent control.

In 1979 we won rent control in the L.A. County unincorporated areas, but it had a sunset clause. Every year we had to fight to keep it, and when a conservative majority with Pete Schabarum, Mike Antonovich, and Deane Dana took over the five-member Board of Supervisors in 1980, they swore that they would repeal rent control. That’s when we knew we had to take rent control out of their hands. So in 1982, CES helped create a group called OUTCRI—Organized and United Tenants for Countywide Rent Initiative—and embarked on a rent control ballot initiative campaign. It included the Marina Tenants Association, the Golden State Manufactured-Home Owners League, and the West Hollywood CES chapter. In November 1983 the ballot initiative Proposition M was on the ballot. The landlords raised over $1 million and the measure lost sixty to forty— except in West Hollywood, where we won five and a half to one.

A week before the Proposition M election, I got a call from Ron Stone trying to develop an effort to incorporate West Hollywood as a city to have local control over zoning, pool hours, minor issues. He was looking for CES’s support. I said, “Look, Ron, good idea, let’s see how Measure M turns out and we’ll get back to you.” After we lost Prop M, CES members Audrey Isser, Helyne Landres, and myself joined Ron to create the West Hollywood Incorporation Committee. We met at Bud and Margot Siegel’s house. We voted Ron as chair and Audrey as vice chair. The uniting issue for all of us was self-rule. CES pushed to have actual organizations represented on the Incorporation Committee, so we brought in Valerie Terrigno, who was president of the [LGBTQ+] Stonewall Democratic Club; Marc Bliefield from the Harvey Milk Democratic Club; and John Heilman from the American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU]. Marc and John played a key role there. They were very progressive and unifying, and always had our backs. The interesting thing is that the gay establishment at that time—including David Mixner and Sheldon Andelson—opposed Cityhood because they had relationships with Ed Edelman and feared that their power would be undercut if Cityhood passed.

The Incorporation Committee decided that CES would take responsibility for gathering the signatures to get Cityhood on the ballot. We were under the gun to get on the November 1984 ballot since the Board of Supervisors had voted to phase out rent control at the end of that year. I kept the petitions with the signatures underneath my desk and counted them every day, making sure that we were on track to qualify for the ballot. As the deadline approached, we were short, so I spent the next two weeks at Alpha Beta [supermarket] on Fairfax, now Whole Foods, getting signatures from morning into the evening. West Hollywood was about eighty-eight percent renters at the time, so all they needed to hear was that their signature would help protect rent control, and they’d sign. Even Demi Moore [actress], who was shopping at Alpha Beta one day, signed our petition. We got the required signatures in record time. I think it was fifty-two days.

The next step to getting Cityhood on the ballot was to go before the Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) to determine whether West Hollywood could sustain itself fiscally. That’s when the landlords became born-again rent control advocates and started putting pressure on the Board of Supervisors to extend rent control. They feared that if Cityhood passed, the West Hollywood City Council would pass a law stronger than L.A. County’s.

Once LAFCO’s report showed West Hollywood was fiscally viable, it took three supervisorial votes, a majority, to approve LAFCO’s findings and put Cityhood on the ballot. The conservative Board of Supervisors’ majority decided to undermine liberal Supervisor Ed Edelman, an opponent of Cityhood, and placed it on the November 1984 ballot. With a November election set, CES moved into campaign mode. That June, the Olympic torch was coming through West Hollywood, so we decided to stand on the corner of Santa Monica and Fairfax with a big banner that said, “Welcome to the future city of West Hollywood.”

Since West Hollywood residents would simultaneously vote on Cityhood and for five City Council members at the same time, CES had to put together a slate of candidates to ensure that we had a strong pro-rent control majority on the City Council. We chose three CES members to run for council who reflected West Hollywood’s diversity: John Heilman, a gay activist and ACLU member; Helen Albert, a senior activist and retired union teacher; and Doug Routh, who was the CES chapter chair, a union member, and Jewish. We left two slots open because we wanted people tripping over themselves to get on the CES slate. Eventually, we added Alan Viterbi—he had connections with the Jewish community—and then Valerie Terrigno—so we’d have a lesbian leader on our slate. The beauty of the campaign was the working together of young gays and lesbians, seniors on fixed income, and others who were threatened with eviction and rent increases.

Most of our members who were at the forefront of the Cityhood campaign had a history in progressive activities—in LGBTQ+, workers’ rights, and fair labor issues, as well as fighting McCarthyism in the 1950s. They were not coming into a fight like this for first time, though we were able to bring in campaign volunteers who hadn’t been involved before. There was this guy Elliot Ingber who was the original lead guitarist for Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and wrote the song “Don’t Bogart That Joint,” which was in the film Easy Rider. And there was Abbe Land who at the time was trying to build an acting career and worked catering jobs. I remember the first time Abbe called the CES campaign office. It was just after nine p.m. and on a fluke, I picked up the phone because I usually didn’t answer it that late. I heard, “Hi, this is Abbe. I’m interested in rent control and fighting for Cityhood.” I often wonder where Abbe would be today if I hadn’t picked up the phone that night [she ended up serving on the City Council for decades].

The work that CES did in West Hollywood for seven years prior to the election—building a grassroots constituency—ensured the Cityhood effort would be a success. There was all this activity, with people doing bumper stickers and other events in the community, but CES had professional consultants and had a community base with targeted voters. No one else was capable of running such an effective campaign. I remember the day before the election, the landlords hired the right-wing Jewish Defense League to leaflet West Hollywood attacking me. The leaflets said that I was the puppet master of the candidates; that I was getting money from Fidel Castro; and that because one of our candidates was affiliated with the ACLU, Nazis would be marching down Fairfax Avenue. I wasn’t even on the ballot, so attacking me was interesting. Still, Cityhood passed on November 6, 1984, and the CES slate won four out of the five City Council seats. Doug came in sixth after Steve Schulte, a gay activist.

While there was a lot to celebrate that night, we were also depressed because Republican Ronald Reagan won the presidency. We thought we could use the new city of West Hollywood to fight Reaganomics. In some ways, the council did that. As a city, all the revenue generated in West Hollywood stayed there instead of going to L.A. County. Thus, the West Hollywood City Council was able to provide residents with the services that were cut as a result of Reaganomics.

I knew there was going to be trouble when the day after the election, Valerie Terrigno called a news conference at the Bel Age—a hotel owned by Severyn Ashkenazy, who was anti-rent control and provided her with a suite at the hotel. It seemed that her interests were not CES’s. But at the first City Council meeting, Valerie was chosen as mayor, since she was the top vote-getter. That meeting was historic. News reporters came from all over the world because people said, “Oh it’s a gay revolution,” due to the fact that a gay majority was elected to the City Council. But they were really elected because they supported rent control. That was the true motivating issue for Cityhood. And as promised, the City Council passed a rent rollback and rent freeze. I remember sitting on the stage with a Village Voice reporter and she understood that Cityhood was about economic justice. She then wrote an article that reflected that. I can’t think of any other city that was actually created around rent control or economic justice.

Right after that first City Council meeting Sheldon Adelson—who was anti-Cityhood but ran the local Bank of Los Angeles and was a Democratic Party heavy-hitter nationally—asked me to have lunch at the Beverly Hills Hotel Polo Lounge. I said, “No, the Polo Lounge is not my style,” so we met at the Greenery Cafe on Santa Monica Boulevard. Sheldon was concerned about his sphere of influence with the council and apparently believed that he had to deal with me. At coffee, he asked me if there was “anything” I wanted. I said, “No, I’m fine,” and made a point of paying for my own coffee. I never heard from him after that.

In the months after Cityhood, the CES Steering Committee worked with the councilmembers and their staff to put forth the most progressive platform we could, and that included a strong rent control law, a domestic partnership ordinance, and a proposal on divesting from South Africa, which served as a model for other cities. Our members served on the various City commissions. We succeeded in getting the City to hire the consultant we wanted to write the rent control law, but when key votes came up, John [Heilman] and Helen [Albert], who advocated for the strongest rent control, were outvoted three to two. It took a year or so to pass the actual rent control law. During this time, the landlords started painting their apartment buildings red to say West Hollywood was the People’s Republic of West Hollywood, and that Cityhood was a Communist insurrection. It ended up being a really a strong law, which had some unique features to it that other rent control laws didn’t—like the maintenance provisions and vacancy control with a ten percent cap increase.

I think it’s important that people remember the role CES played in Cityhood. In memory of all our members who spent hours upon hours, days upon weeks ensuring that West Hollywood became a city, I think of the unsung heroes of this fight that will never be recognized—like Jacqueline Balogh, Carole Hossan, Frances Eisenberg, Ann Polsky, Elizabeth Burns, Joe Thompson, and others. They’re the ones who really created this city. West Hollywood represents what can be achieved—that people can accumulate political power and create a city. The West Hollywood Cityhood story is a story of hard work and grassroots and long-term visions: we took the defeat of Measure M and turned it into a victory. It’s an example of why people should not be discouraged and should understand that these battles are long-term.